REVIEW: A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen

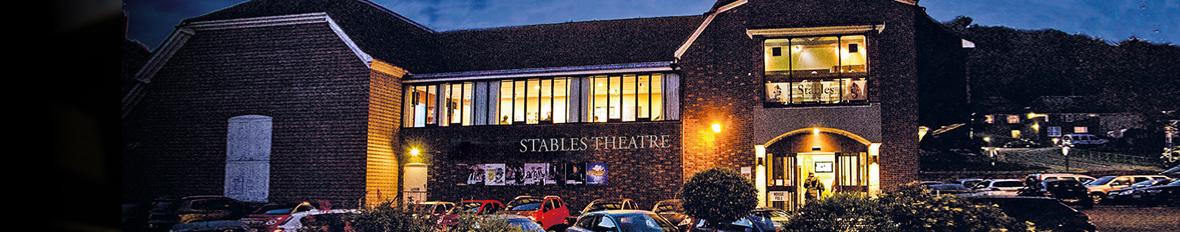

A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen is one of the great names on theatrical bookshelves, one of those plays that you are embarrassed to admit that you’ve never seen before. So it was with some anticipation of a really good play that I went to see director Sandra Tomlinson’s opus on its opening night.

As it turned out, this was among the finest productions that I have seen at the Stables Theatre. First and foremost, Elly Tipping as Nora pulled off a tour de force. Never faltering, she played the eponymous “doll” to perfection, skittish and nervous, emotions almost palpable and motives always suitably ambiguous. David Drey as her husband Torvald was superb, portraying a character who was superficial, weak and unlikeable, perfectly judging the fine line between over- and under-playing the role. I gather that by the end of the run his voice had fallen foul of a lergy, but there was no sign of this on day one.

For Mike Stoneham as Krogstad, the task was to appear vile until a softening at the end under the capable manoevering of Kristine (Jackie Eichler). Both of these characters were entirely plausible in their human struggles, and here too the man appeared as the weaker of the two, being reduced to low behaviour when let down by a woman, only to be restored to nobility under a fresh appeal to his emotions. Dominic Campbell in the role of Dr Rank played his role perfectly, his disability portrayed consistently, modest and emotional but finally denied by the woman.

There were no weak performances. Anna the nanny (Janet McCarter), Helen the maid (Cleo Veness), and the two boys Jon (James Greenhalf) and Ivar (Toby Mocrei) all slotted their roles in subtly, never stealing unwonted limelight but supporting the action confidently and capably.

The set was a masterpiece of Victoriana – all credit to the designer Frank Jenks and the extensive set construction team – and the sound design and operation (Andy Bissenden and Ryan Norcott respectively), lights (that fireplace!) and costumes (Gill Jenks) were also virtually faultless.

The message of this play is threefold: Beware of setting yourself up as powerful and important, if you are not prepared to behave in accordance with your stringent moral principles; beware of underestimating the capabilities of people who are in a weaker position; and beware of not going to every Stables Theatre production, because you might miss a play as good as this.

Margaret Blurton